The modern world is not “secular” by chance. It is also the result of a great religious formation. I have made the case elsewhere that the secular world is actually “religious” in its manifestation, and I hold to it. In this article, I will be using “secular” and “religious” in their typical modern juxtaposition. One of the most prominent influences on the modern American religious mind, and by extension the “West,” will be examined in this piece and subsequent ones. This movement introduced a radical paradigm shift. It originated in the Protestant world and has subsequently influenced even the monolith of Rome. Much of what may be called the “secular mindset” has been influenced by this religious movement.

It is undeniable, whether one is an Atheist, a Theist, a Protestant, a Roman Catholic, or Orthodox, that the mentalities of what I will generally call the Evangelical Pentecostal-Charismatic movement have had a substantial influence on the modern religious expression of the 20th and 21st centuries. This is vital to understand. This movement introduced an overwhelming and novel influence on Twentieth-century Christian (I use “Christian” in a very general manner) thought and praxis. It is vital to understand that this movement has aided and shaped the prominent contours of the modern world and a novel religious mindset within Christianity.

I am a former Evangelical Charismatic. I was raised in the Vineyard Christian Fellowship, where my dad was a minister for a time. As a young boy, I remember running around the offices of the Anaheim Vineyard. I remember goofing around with John Wimber (founder of the Vineyard). I grew up in a “prophetic/charismatic” environment. Lonnie Frisbee, Bob Jones, Paul Cain, etc. (some purported “prophets”). Some of them I knew fairly well because of my dad’s position as a minister (keep in mind this was in my childhood and adolescence).1 If these names mean nothing to you, don’t worry about it. Suffice it for you, the reader, to know that back in the day, these were big names in their circles. My generation was constantly told that we would change the world for Jesus. It all seemed pretty exciting at the time. I spent three years in the mission field, in Kharkov, Ukraine (where I met my wife). From there, I went to Brownsville Revival School of Ministry (BRSM), located at an Assemblies of God church in Brownsville, Florida. I was part of the “pioneer class.” The school was centered around what was called “The Brownsville Revival.” Manifestations? Check. Speaking in tongues? Check. Slain in the Spirit? Check. Prophetic words? Check. Dreams? Check. Visions? Check. Anyway, you get the point. My faith was quite Pentecostal and Charismatic in its expression. Shortly after I graduated from BRSM, and while in the midst of pursuing Protestant ministry, the discovery of the Orthodox Church delightfully sidetracked me. But that is another story.

I went from an environment that valued “spontaneity in the Spirit” to liturgical worship and Tradition. It seemed like two different worlds. I had a lot to process. My focus at present is to offer some of the examinations and conclusions that I have worked through and arrived at, in the hope that some may gain benefit from them (I entered the Orthodox Church in 2003).

I will focus primarily on history, method, and underlying meaning. I will strive to avoid polemics, but in such an endeavor, it will be difficult to evade them entirely. Let me state from the start: my goal is to address systems. I leave all persons to the judgment of God. Nonetheless, we are called to test, discern, and pass judgment, as St. John says, Do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see if they are of God (1 Jn. 4:1). Moreover, there are concrete Christian standards by which to make such judgments, and they are not subjective. Thus, it is vital to understand, identify, and evaluate the origins and roots of the modern Charismatic movement.

Towards an understanding of the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement

The Pentecostal/Charismatic movement has penetrated almost every sector of modern Christendom. From Baptists to Roman Catholics. Only in the Orthodox Church has it not found a firm place to grow, although it has tried to find a foothold. Christianity Today states, “A 2011 Pew Forum study showed that almost 305,000,000 people worldwide … (are) part of the charismatic movement.”2 (If both Pentecostals and Charismatics are considered together, the number is close to half a billion). The mindset that the movement embraces has influenced much of the modern Protestant mind (post-1900s). It’s important to note that the modern Protestant/Charismatic expression fundamentally diverged from what might be simply called a “classic” Protestant form. In the following, I will briefly overview the historical roots of the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement (referred to as P/C movement from here on for the sake of brevity). Ah, history. For many a modern person, it is not too horribly important; we do love to exist in our ahistorical virtual world. Nonetheless, we arrived where we are today by very distinct paths. To begin to understand the modern “Charismatic” experience, we must examine history – its roots and paths.

Before we delve into history, we must understand a particular principle that drives much of modern Evangelical Protestantism, most of all those sectors embracing the P/C movement. This mindset has been called “Emerging Church.” It also has other names, such as Restorationism, Kingdom Theology, Third Wave, and so forth; there may exist surface differences, but the underlying essence and foundation of these teachings are very similar. I have before me school notes from my BRSM days (yes, I am one of those people who have saved school notes), which present a basic sketch of the general Emerging Church philosophy.

They go as follows: between the year 311 AD and 1300 AD is simply the word “Darkness” (from 33AD to 311AD the church was said to be operating in its original “power”). This teaching claims that the Church entered a time of captivity and darkness starting around 311 AD. 1300 AD is labeled “Refreshing Starts.” During this period, figures such as John Huss, John Wycliffe, and others are considered the pioneers of “refreshment.” 1500 AD is labeled – “Grace,” clearly this refers to what is known as the Protestant Reformation. 1700 AD – “Personal holiness and conversion.” 1800 AD – “Prayer and Evangelism.” 1900 AD – “Baptism of the Holy Spirit.” 1950 AD – “Charismatic.” Late 1900s – “Combine them all!” The note below the diagram reads, “God is building, adding and adding, God is restoring His Church!” And with a note of surprised delight, it comments, “In the 1950s and after charismatic gifts began to flow even in the traditional churches.” To recap, the church was operating well for the first 300 years, fell into darkness around 311 AD, and an event called the Protestant Reformation began to restore original and authentic Christianity.

The reader may already perceive, the clear conclusion is that the Church (using that word very loosely) was lost to darkness, but eventually, God stepped in and overthrew the “traditions of men” to reestablish His work. The clear implication is that most of the Church’s history between roughly 300-1500 AD was not of God; it was the work of men. I remember it being explained through the analogy of a puzzle: the puzzle was broken, the pieces were lost and scattered, but they are slowly being put back together, and the result will be the restoration of the full picture – a great move of God in “signs and wonders.” The school notes continue, “We can expect a last surge to parallel (or even surpass) the first.” That is, there will be an “outpouring” that may even surpass that of the Book of Acts. This is why “revivals” play an important role in this mindset. This is also why it generally distains anything that it considers “traditional.”

Thus, this mindset holds no substantial value for tradition (or actual history). Tradition, such a paradigm commonly holds, was the death of the early Church. It became the human supplement to the original power and freedom in the “Spirit,” which was initially at work in the early Church but subsequently lost. This mindset typically ignores the many positive references to tradition in the Scripture (for example, 2 Thess 2:15) and rather elevates subjective experiences to the level of dogma. Individual experiences and ideas are projected as new standards of faith. This helps in part to explain why there exist thousands of varying protestant groups. It also cultivates the mentality that a person just needs their own faith in Jesus. The concept of the church is trivialized to be practically unnecessary.

I believe that the “Emerging Church” ideology reflects a type of “Christian” spiritual evolution. It is, I would venture, influenced more by the Western European philosophy of Progress, which was developed during the “Enlightenment,” than by anything in the Scripture or Christian history. Such a mindset holds that almost everything old is bad or outdated, and the “new” is what is sought after (in the form of the next “move of God”). It is a christianized (if even possible) Übermensch. People, and the church, are progressing toward the spiritual “superman.” Christianity is evolving towards the final and greatest revelation and “revival.” Currently, I will not wander into the Scriptures that Emerging Church adherents use to substantiate their claims. I may address this later on. The focus at hand is historical formation.

The P/C movement did not take place in a vacuum. It certainly could be traced back to the “Revival Holiness” movements of the 1800s in America, and beyond. It is a manifestation of DNA that has been in Protestantism since its inception in the 1500s. I will not follow that stream at present but will focus on the visible birth of the P/C movement at the turn of the 20th century. Two key figures will be surveyed: Charles Parham, who is called “the father of Pentecost,” and William Seymour, who is considered “the catalyst of Pentecost.” Clearly, numerous other individuals were involved in the movement, but for the sake of expediency, I have narrowed it down to two of the most prominent.

Charles Parham

Mr. Parham began his ministry in the healing “revivals” of the late 1800s. As with many of his time, he professed to have a deep hunger for God and a profound desire to see the moving of the power of God. Similar to other figures of that period, he became disillusioned with “denominationalism.” It is an interesting side note that similar sentiments were expressed by both Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, and Charles Taze Russell, the founder of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. This is not to directly equate these three men; Mr. Parham clearly never outright denied the Divinity of Christ, as did the latter two. But the reader should note that a spirit of discontent existed within “denominationalism” in the 1800s, and many figures arose claiming to restore “true” Christianity. They continue to do so to this day. All three of these men professed to be seeking a new and special coming of Christ and His Kingdom; each one claimed to have received a divine and unique revelation. Mr. Parham states, ” … Feeling the narrowness of sectarian churchism, I was often in conflict with the higher authorities, which eventually resulted in open rupture; and I left denominationalism forever, though suffering bitter persecution at the hands of the church … Oh, the narrowness of many who call themselves the Lord’s own!” (Liardon, Robert. God’s Generals, Albury Publishing, 1996. p. 115.) Through subsequent experiences, he became convinced that “there still remained a great outpouring of power for the Christians who are to close this age” (Ibid, p. 117).

Parham eventually opened his own Bible school in Topeka, Kansas, and later another in Houston, Texas. At one point, he gave his students an assignment to diligently study the Scriptures (with a focus on the book of Acts) for evidence of the baptism of the Holy Spirit. After three days, the account goes, all the students (forty in all) came to the same conclusion: the common manifestation of baptism in the Holy Spirit is “speaking in tongues.“ Fixated on this manifestation, they resolved to pray until they received the gift of tongues. A student by the name of Agnes Ozman is reportedly the first to receive the “gift.” Accounts say that she spoke in Chinese. In the very early records of the P/C movement, tongues are described as being in some known earthly language. Mr. Parham says that he received the gift of the Swedish tongue. I will not address here the gift of tongues and the Orthodox understanding of it, but it should be taken into account that the very early P/C movement did not claim to be speaking in unintelligible babble, but, as we will see, it very soon turned into that very thing. Another striking point is that this “outpouring” comes right at the start of the 20th century, which will be a century of unparalleled change and world upheaval. ( St. John of Kronstadt’s prophecy helps an Orthodox Christian understand many of the events of the 20th and 21st century, found here – https://www.imdleo.gr/diaf/files/english/St_John_Kron/st_john_vision.html )

Parham then began to preach “the baptism of the Holy Spirit and the evidence of tongues.” His teaching is the foundation for the Pentecostal doctrine of tongues as the initial sign of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit. That is, speaking in tongues is the very proof of being “filled with the Holy Spirit.” Such a doctrine was unheard of in Christianity before this time. Although isolated instances of “speaking in tongues” were recorded within Protestantism before Mr. Parham’s movement, his movement is responsible for its growth and even explosion in the Protestant world and beyond.

Many phenomenal stories and accounts surround the life of Mr. Parham. He sincerely saw himself as restoring the apostolic faith, “Now that they [apostolic faith tents] are generally accepted, I simply take my place among the brethren …” (Ibid. 128). Like many other Protestant leaders before him, he was confident that God had chosen and entrusted him with a unique task – the revival of true Christianity. He was willing to write off his opponents as narrow-minded and opposed to the will of God (as he proclaimed it). Ironically, in his professed desire to escape the confines of “denominationalism,” he created a new denominator: Pentecostalism. Thereby perpetuating the very fracturing that he allegedly wished to heal. Mr. Parham claimed that his authority was derived from the Bible and the power of the Holy Spirit. Like most Protestants, he subscribed to “Sola Scriptura” (the teaching that the Bible alone is necessary for establishing Christian Faith). But, as most of Protestant history shows, there was significant disagreement on what the Bible supposedly simply and clearly proclaimed. It was not so clear and simple after all. Pentecostalism would have an ever-evolving body of various teachings, many of which contradict each other. Accusations of sexual immorality plagued the end of Mr. Parham’s ministry.

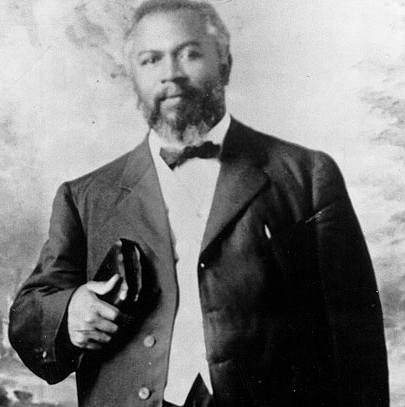

William J. Seymour

Mr. Seymour was an African American Baptist minister turned holiness preacher who also professed dissatisfaction with the Christianity of his day and sought a deeper experience. He had wandered through a few denominations before he stumbled upon Mr. Parham’s meetings in Houston, Texas. He attended Parham’s school in Houston. Due to the segregation of the times, Mr. Seymour was not able to sit in the classroom; instead, he listened to the lectures from the hallway. One writer states, “Though Seymour did not embrace every doctrine that Parham taught, he did embrace the truth of Parham’s doctrine concerning Pentecost. He soon developed his own theology from it” ( my emphasis, Ibid. p. 143).

In 1906, Seymour made his way to Los Angeles, California, where he took a pastorate job. He immediately began to preach his newly found doctrine of speaking in tongues. As with the group in Topeka, Seymour and company spent hours seeking the “baptism of the Holy Spirit.” At some point, a Mr. Lee began speaking in tongues, followed by others. People ran around purportedly prophesying and preaching; others claimed miraculous healings.

The group eventually found a building at 312 Azusa Street, and thus to this day the event is frequently referred to as the “Azusa Street Revival.” The meetings are described as “unique:” the seating was arranged so that the participants faced one another (similar to the practice of Quakers). The music was impromptu, no hymn books were used, and the meetings had no program, leaving everything to the “direction of the Spirit.” When the group thought that someone was not speaking from the “Spirit,” they would begin to wail and sob. In a publication called The Apostolic Faith, “Seymour announced his intention to restore ‘the faith once delivered’ …” (Ibid. p. 154). As with Parham, the implication is obvious: the Apostolic Faith had been lost, and these men were those chosen to restore it. At Azusa Street, the alleged manifestations of the “Spirit” quickly began to take on unnatural symptoms: tongues became unintelligible babble, called a “prayer language.” Participants also howled, writhed, shook, wailed, and were seized by fits and spasms, and so forth. Azusa Street is the fount of every P/C manifestation that continue down to this day. Almost every Pentecostal denomination, whether directly or indirectly, traces its founding to the participants of Azusa (Ibid. p. 163).

Very quickly, the move of the “Spirit” that was to unite all true believers began to fragment into rival factions. At some point, Mr. Parham traveled to the Azusa Mission, and there he relates in horror what he found, “I hurried to Los Angeles, and to my utter surprise and astonishment I found conditions even worse than I anticipated … manifestations of the flesh, spiritualistic controls, saw people practicing hypnotism at the altar over candidates seeking baptism, though many were receiving the real baptism … I found hypnotic influences, familiar-spirit influences, spiritualistic influences, mesomeric influences, and all kinds of spells, spasms, falling into trances, etc.” (Ibid. 157,158). He also reproached it as “spiritual power prostituted.” At least Mr. Parham had the sense to understand, “The Holy Spirit does nothing that is unnatural or unseemingly, and any strained exertion of body, mind or voice is not the work of the Holy Spirit, but of some familiar spirit, or other influence. The Holy Spirit never leads us beyond the point of self-control or the control of others, while familiar spirits of fanaticism lead us both beyond self-control and the power to help others” (Ibid. p. 158). The “father of speaking in tongues” himself denounced the work at Azusa as unnatural.

One would think this to be a crushing blow to Seymour and his followers, but it was not. Seymour merely banned Parham from the meetings, stating, “Mr. Parham … is not the leader of this movement of Azusa Mission. We thought of having him to be our leader and so stated in our paper (The Apostolic Faith), before waiting on the Lord. We can be rather hasty, especially when we are very young in the power of the Holy Spirit …” Apparently, Seymour implies that he has now surpassed Parham in his understanding of the “Power of the Spirit.” The Azusa Mission disregarded Parham’s criticisms and claimed to have outgrown his unenlightened and immature thoughts. As with ensuing groups, they saw themselves as much more enlightened and filled with the “Holy Spirit,” and thus were under no obligation to obey “men.” Such a claim, of course, only becomes a convenient cover for pride and arrogance, which are always present in such “moves of the Holy Spirit.” A leader simply claims to be more in tune with the “Spirit” than those before him. He becomes the one who properly understands the things of the “Spirit.” In Orthodoxy, this is called prelest.

Most of the more stable and classic Evangelical ministers of the time denounced the movement: “G. Campbell Morgan, a highly respected evangelical preacher, called the Pentecostal movement ‘the last vomit of Satan,’ while R. A. Torrey claimed that it was ’emphatically not of God, and [was] founded by a Sodomite.’ In his book, Holiness, the False and the True, Harry Ironside, in 1912, denounced the movement as ‘disgusting . . . delusions and insanities’ and accused their meetings of causing ‘a heavy toll of lunacy and infidelity.’”3

These fiercely denounced subjective and novel experiences are the central bedrock of “theology” for the P/C movement.

With Parham, the “Pentecostal” experience began in a manner that would be somewhat acceptable to a certain sector of Protestants, but once it gained traction, it quickly revealed its true nature: one that was unveiled at Azusa. Unaccountability, bizarre manifestations, and such things all found a happy home under the excuse of “the Spirit is leading me and the Bible says so.” Such “freedom” is irresistible.

The Azusa Mission quickly fell into disarray and division. Seymour’s various “disciples” rose up to claim a deeper “experience of the Spirit,” much as Seymour had done with Parham. Seymour ended his days with a shell of a movement after consecutive splits and fractures only about twenty people remained with him at the original Azusa Mission.

Charismatic movement

The Charismatic movement approximately marks the point when “Pentecostal” teachings and manifestations began to surface in “Mainline” denominations. It is critical to understand that the Charismatic movement in all its variety is a direct descendant of the Pentecostal movement. That is, the Charismatic movement is directly founded in the Pentecostal movement. Before the Charismatic movement, “Pentecostals” were considered “fringe groups” by many classic Protestant denominations.

Most sources consider Mr. Dennis Bennett as the vanguard of the charismatic movement. He was an Episcopal minister in Van Nuys, CA. In 1960, he claimed to have experienced the Pentecostal “baptism of the Holy Spirit.” Due to the conflict that this created in his congregation, he resigned and took another Episcopal church in Seattle, WA., named St. Luke’s. This community became a center point in the early charismatic movement. “In a sense, Pentecostalism was entering the mainline (the Episcopal Church, no less) and this was news. This began the mainstreaming of continualist practices (like speaking in tongues, praying for healing, etc.) that were primarily found in Pentecostal churches that, up until now, were often on the fringe of Protestantism.”4 Pentecostalism, facilitated by this mutation into Charismaticism, quickly spread through “Mainline” Protestantism, and it did not stop there. It even made its way into the Roman Catholic Church (where there are estimated to be around 115 million Charismatics). “Though much of the belief and practice of the Charismatic Movement came directly from the Pentecostals who had been around for nearly sixty years, the mainline churches who embraced such belief avoided the ‘Pentecostal’ label for both cultural and theological reasons.”5

“This new ‘Charismatic’ movement quickly spread to other mainline denominations and, by the mid-’60s … The movement’s visibility and networks were further strengthened by the success of the Pentecostal-leaning “Jesus People” movement among American youth in the late ’60s and ’70s. In the 1980s, a vigorous, independent network of Charismatic churches and organizations (at times described as the “Third Wave”) emerged, including churches such as the Vineyard Christian Fellowship.”6

Thus, the Charismatic and Pentecostal movements, and their subsequent mutations, are indeed one cohesive movement. These subjective movements have, through various means, become some of the most influential mindsets in the modern Christian world (again using “Christian” in a general manner). The thought and teaching of what I generally label “Evangelical Charismaticism” has come to be one of the most dominant features of modern Protestantism (and to a degree Roman Catholicism).

As I move forward with this series, an important question to ask is: Did the ancient and early Church confront any phenomenon similar to the P/C movement? Did the Pentecostal movement authentically restore the “power of the Holy Spirit” and “Biblical worship?” Or did it simply remanifest ancient spirits of error that true Christianity had long ago addressed and dealt with? I will investigate these questions in a subsequent post.

1My Father, Mother, and my two siblings have since converted to Holy Orthodoxy. My Father is currently a priest.

5Ibid.

Pingback: A New Charisma in the Early Church – The Inkless Pen

Pingback: Is Christ Faithless? Examining Protestant Ecclesiology – The Inkless Pen

Pingback: A Last Days Great Revival …? – The Inkless Pen

Wow. A lot here for me to digest. Craig Anderson

LikeLike